Opening Reception: Friday, April 26th, 6-8pm

Auxier Kline is pleased to present Hank Ehrenfried’s third solo exhibition at the gallery, Nine and a Half, featuring a survey of new paintings created with the artist’s husband as muse.

Knowing Intimately

Campbell Shiflett

Hank and I have made a project of knowing one another. That is to say, like so many married people, we have committed ourselves to the task of learning what can be learned about the other person. This doesn’t mean we try to know everything. Even if such a thing were possible, how much a person knows about their partner is hardly the measure of a relationship. A relationship’s depth (an inapt word) is not quantitative.

Nine and a half years together have taught me to think of our relationship in terms of intensity, to understand its course not by the quantity of our knowledge but the quality of our knowing. This I think is the meaning of intimacy: being comfortable with the fact that there is more to your relationship than what you know about the other person, even that there is an aspect of your partnership beyond your knowledge—the part of your partner that tries to know you.

You can imagine how funny it feels for me to have to imagine that perspective in contemplating these paintings my husband made of me.

Of course, the works themselves only hint at how Hank actually sees me. For example, the fact that nearly all of the paintings were done from cell-phone photographs means we see their subjects from a point of view different from the artist’s own. You can observe this yourself in a few of the works where my gaze is directed just above or to one side of the viewer, as I look not at the camera but at Hank’s face behind the phone.

On a more basic level, the translation of his perspective into paint also makes it difficult to discern whether details in the work represent Hank’s perception of me, or whether they have more to do with the properties of his medium. I look at his renderings of my face (all of which resemble mine, but which often do not resemble each other) and wonder from what source the differences arise, but I cannot know. And I am fine with that.

I enjoy these paintings not because they can reveal what Hank sees when he looks at me, but because they document his effort to know me. In that sense, they are not so much portraits as process paintings. So much in the work foregrounds the act of their making: The lay of paint, the busy brushwork, the discrete succession of tones in a patch of skin or fabric or wood. These are evidence of a partner’s work as well as a painter’s.

In this Hank’s portraits of me achieve the same effect as his paintings of collages pinned to walls, though in reverse. There, it is the trompe l’œil rendering that at first entices the viewer to imagine the artist’s perspective. Then their subject matter—juxtaposing images from erotica and cartoons, museum postcards and industrial design catalogues—reveals the artist’s work, his effort to account for the secret histories of his materials by relating them to one another.

Those collage paintings bring together images with lives of their own and grapple with the task of trying to understand them entirely. I cannot help but see something similar happening in these portraits. They testify to the artist’s project to know his subject, but in the process show that this project is different in kind from the mere collection of knowledge. That the work feels so comfortable with this is the source of its intimacy.

Campbell Shiflett is the husband of the artist. He teaches music history at Oklahoma City University.

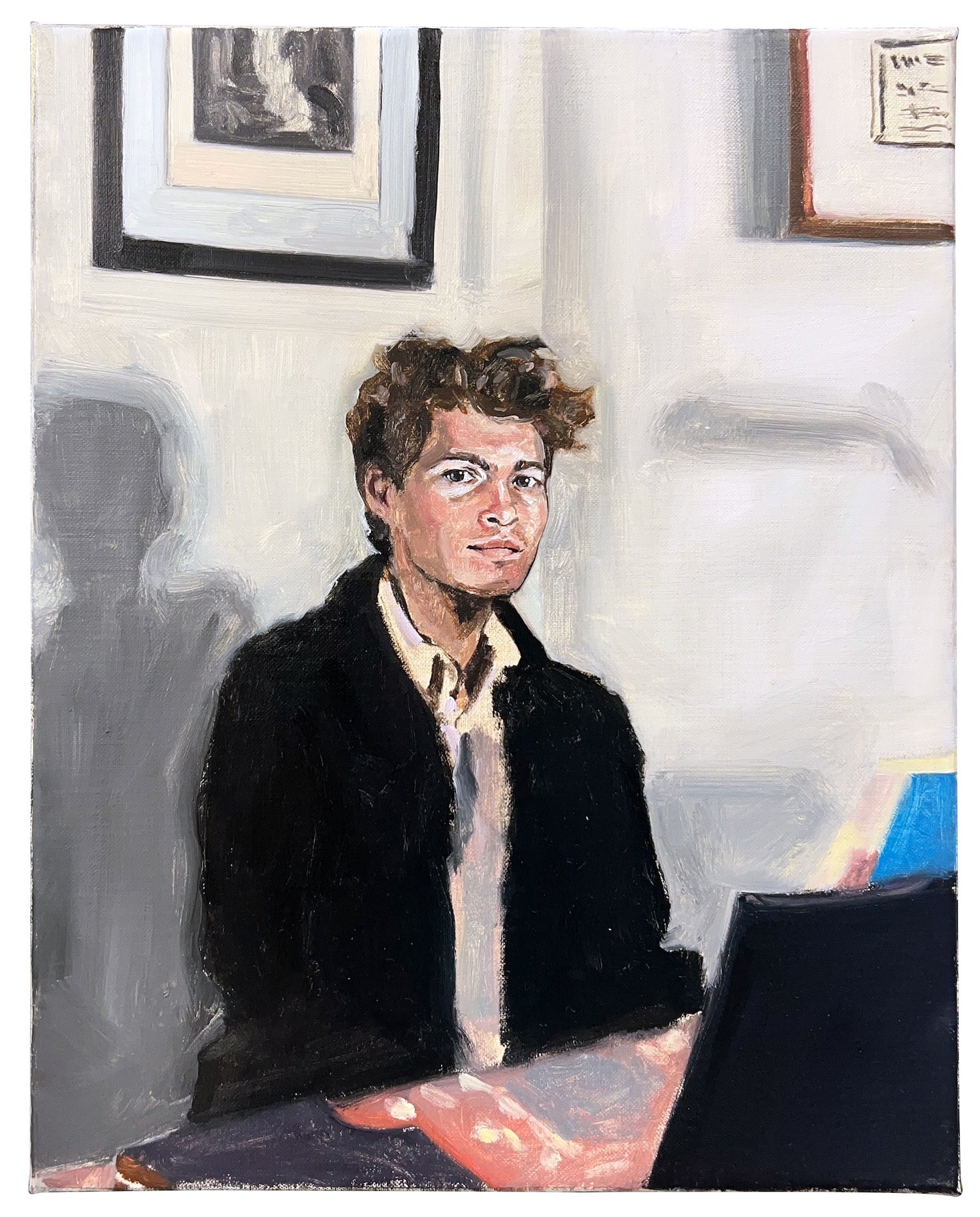

Hank Ehrenfried, "At the Piano in Brooklyn", 15 x 12 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "Campbell in Cassis on our Honeymoon", 15 x 12 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "25 Lafayette", 10 x 8 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "In the Studio", 16 x 20 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "Honeymoon", 15 x 12 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "Snack at Hotel Saint Marc", 15 x 12 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "At John and Erik’s", 15 x 12 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "Campbell at Cannon Beach", 12 x 9 inches, Oil on linen, 2024

Hank Ehrenfried, "At the Piano in Oklahoma City", 15 x 12 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "Masked", 10 x 8 inches, Oil on linen, 2022

Hank Ehrenfried, "In Oregon", 15 x 12 inches, Oil on linen, 2024

Hank Ehrenfried, "Montauk New Years", 15 x 12 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "New Year at Montauk II", 12 x 9 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

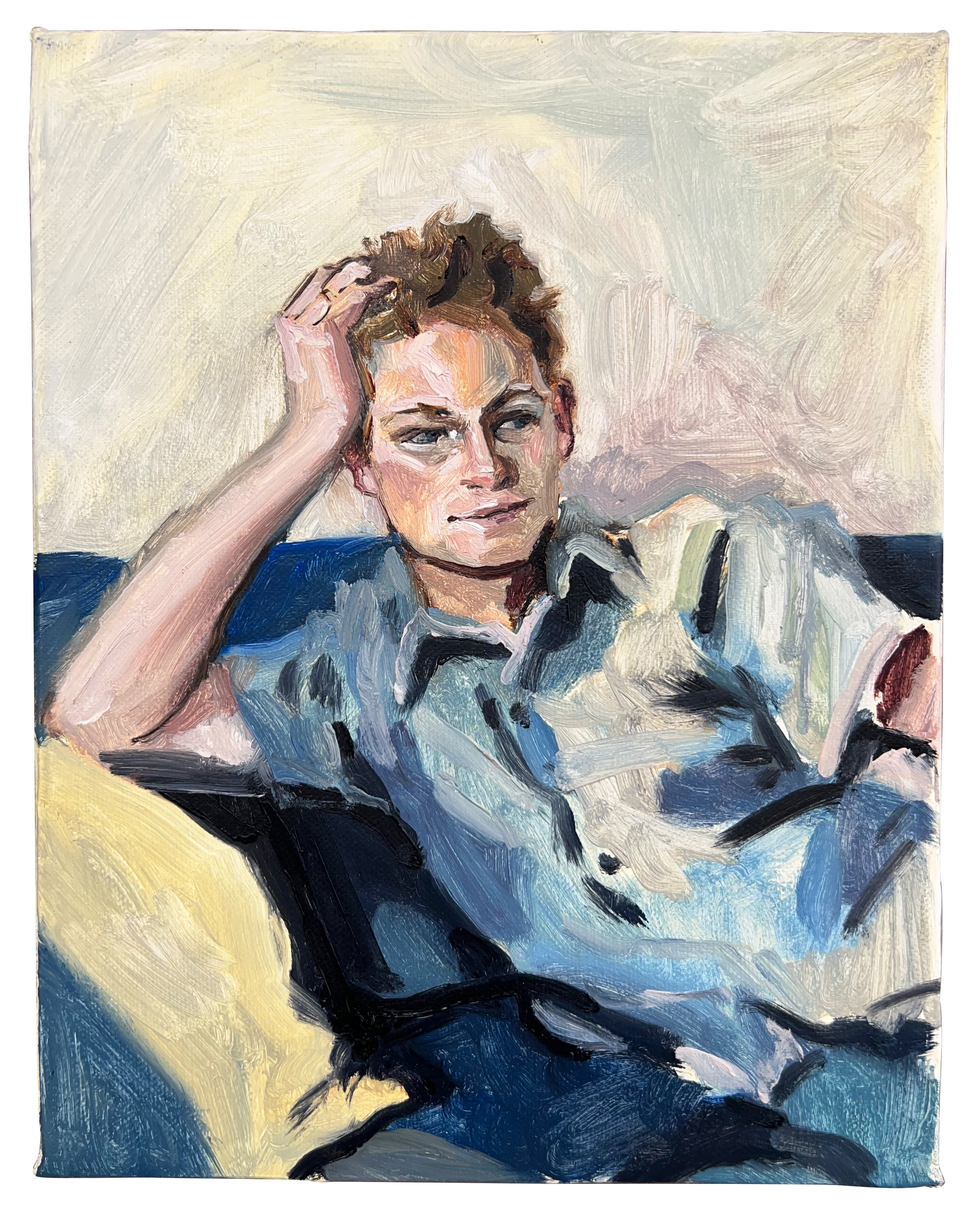

Hank Ehrenfried, "Reclined", 10 x 8 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "Green Pepper Shirt", 12 x 9 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "After Fanin-Latour, 12 x 9 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

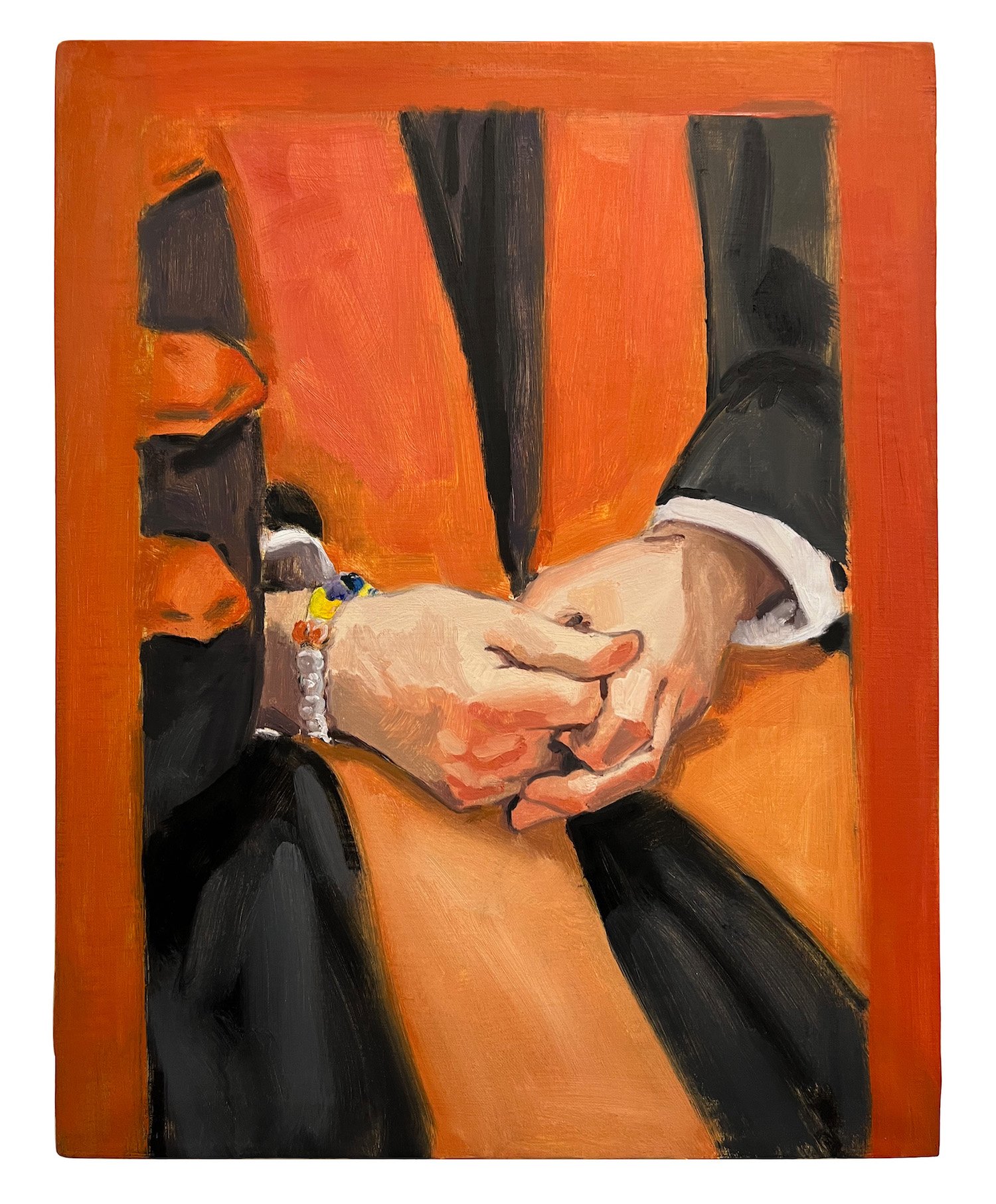

Hank Ehrenfried, "Dr. Campbell Shiflett’s Hands", 20 x 16 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "In the Art Building", 15 x 12 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried, "Swimming at the Calanques", 24 x 18 inches, Oil on linen, 2023

Hank Ehrenfried holds a BFA in painting from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, PA and an MFA in painting from Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY. Ehrenfried is from New Jersey. He is based in Oklahoma City, OK.